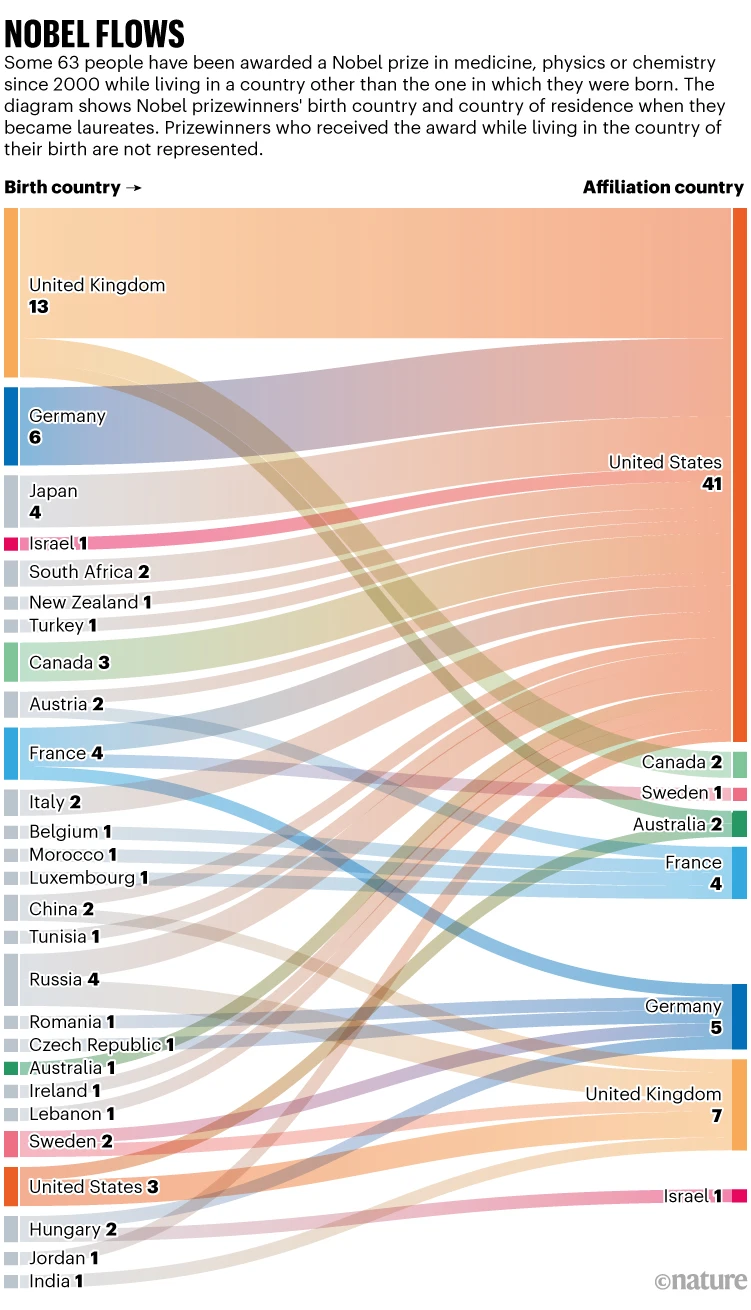

In an era defined by globalization and intensifying technological competition, the movement of scientific talent has become a crucial marker of innovation ecosystems. A recent analysis published in Nature reports that since the beginning of the 21st century, more than one-third of Nobel Prize winners in the sciences have immigrant backgrounds. This finding not only sheds light on the global mobility networks behind scientific excellence but also sparks discussion about talent flows, equity, and the distribution of innovation capacity worldwide.

According to Nature’s data, between 2001 and 2024, hundreds of Nobel laureates were recognized across the sciences—including physics, chemistry, and physiology or medicine—and more than 30% of them lived or worked outside their birth countries at the time of their awards. Some moved for educational opportunities, others sought better research environments, and still others left their homelands due to political or economic pressures. Regardless of their motivations, together they represent a transnational portrait of modern scientific innovation.

The article highlights that the United States remains the world’s primary magnet for scientific talent. Roughly half of all “immigrant Nobel laureates” in the 21st century have settled or worked in the U.S. Institutions such as Harvard University, MIT, and the University of California system have long provided global scholars with resources and platforms that nurture Nobel-worthy research. However, Nature also cautions that this trend reflects a deep imbalance in the global research ecosystem—some nations lose their most promising scientists to this ongoing “brain drain.”

European countries play a dual role in this pattern—as both sources and destinations of talent. The United Kingdom, Germany, and France continue to attract large numbers of researchers from Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, thanks to their strong academic traditions and world-class universities. Yet, as research funding tightens and visa policies become stricter, Europe is also witnessing a steady outflow of young scholars to the United States and other regions with more open research environments.

Notably, Nature’s analysis extends beyond statistics. It emphasizes that the stories of scientific migration illustrate both the necessity and the complexity of global collaboration. From international medical research projects to multi-nation quantum physics experiments, breakthroughs often arise from cross-cultural exchanges and collaborative innovation. As one expert quoted in the article put it, “Science has no borders, but scientists have passports.” This paradox serves as a reminder that scientific freedom depends on institutional and cultural support.

From a sociological perspective, the trend is also reshaping how we understand “national research strength.” In the past, Nobel Prizes were often seen as symbols of national scientific systems; today, many award-winning discoveries are products of multinational cooperation. The map of scientific innovation is shifting—from one of “national competition” to “global collaboration.”

At the end of the article, Nature calls on policymakers worldwide to rethink the relationship between research and immigration policy. Open and inclusive research environments are not only key to attracting top talent but also foundational to advancing global innovation and social progress. This is particularly true in frontier fields such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and climate science, where cross-border collaboration and knowledge exchange are essential.