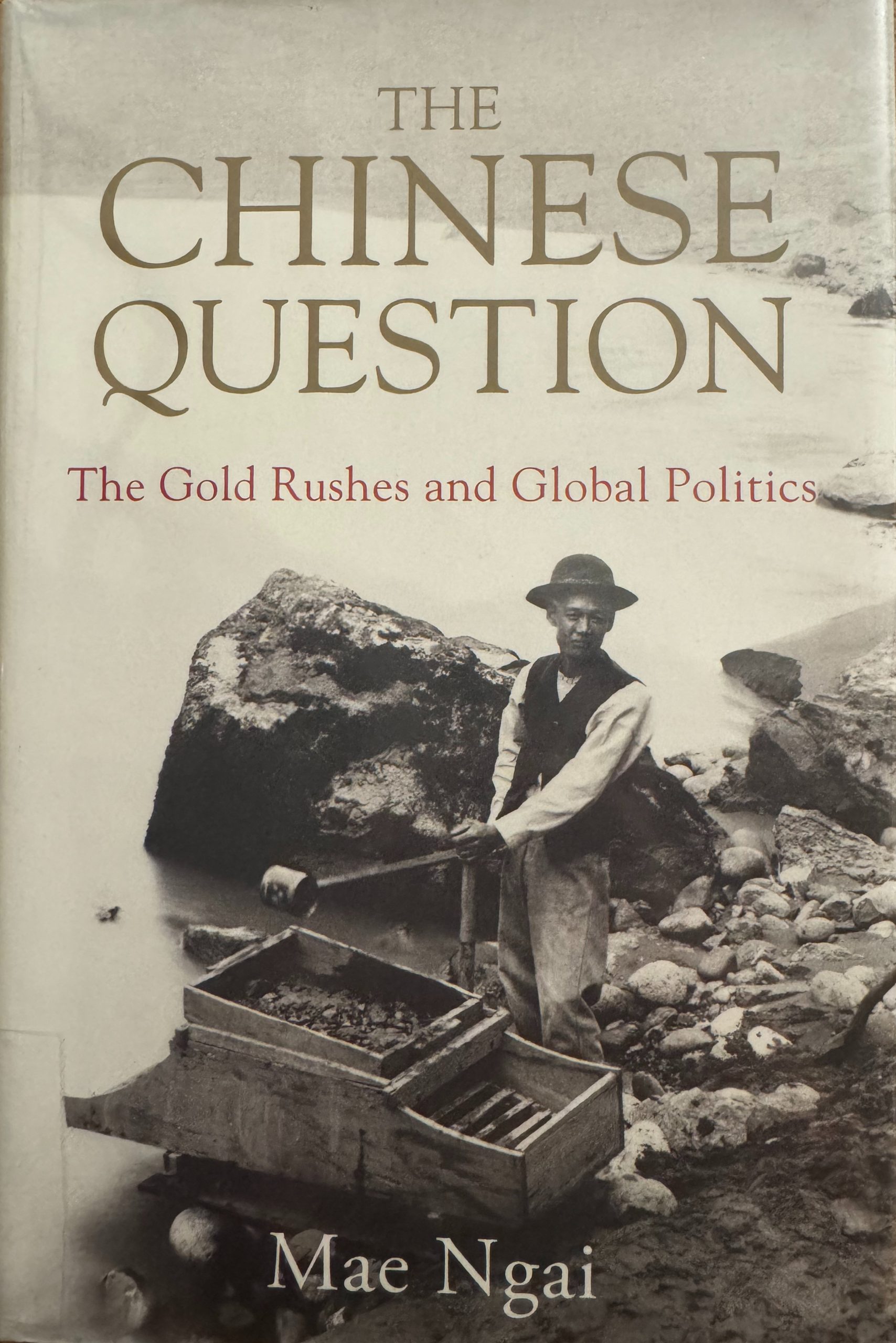

Amid renewed debates over U.S.-China competition, supply chain security, and the so-called “China threat,” the “Chinese Question” has resurfaced in public discourse—not as a new phenomenon, but as one with deep historical roots. In The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics, Columbia University historian Mae M. Ngai shows that Western anxieties about Chinese migrants stretch back to the gold rushes of the nineteenth century, when Chinese laborers crossing oceans became both essential to economic expansion and objects of fear and exclusion.

Ngai situates these experiences in a global context, tracing the narrative from California’s goldfields to mines in Australia and South Africa. The gold rushes, she argues, were part of a transnational capitalist network, where Chinese workers were indispensable yet treated as outsiders. Their efficiency and skill fueled mining prosperity, but also sparked resentment among white laborers. Anti-Chinese sentiment and “white protectionism” emerged almost simultaneously across continents, revealing that exclusion was not incidental but a structural product of imperial expansion and racial hierarchies. The “Chinese Question” was never truly about the Chinese themselves; it was about how Western societies defined the boundaries of their own civilization amid globalization.

Ngai highlights how economic competition was consistently reframed as racial threat. White miners accused Chinese workers of “stealing jobs,” colonial authorities claimed they “disrupted social order,” and newspapers stoked panic with the rhetoric of the “Yellow Peril.” Ngai observes that when Chinese laborers demonstrated competence and diligence, institutionalized racism interpreted these qualities as a threat to white privilege. As she writes: “The Chinese were never the cause of crisis, but the mirror in which the West saw its own contradictions.” Today, as debates over “de-risking,” industrial security, and “Made in China” continue, these historical echoes remain painfully relevant.

Methodologically, Ngai combines labor history, legal history, and colonial studies to reveal the global structures underpinning racial hierarchies. Drawing on mining logs, newspapers, colonial correspondence, and corporate records, she reconstructs a social ecosystem spanning half the globe. Readers can almost see the dimly lit miners’ quarters, hear hammers striking rock, and sense how anonymous laborers were rendered invisible by archival silence. She does not romanticize their suffering; she shows how they survived and adapted in a hostile environment, making history vivid, complex, and real.

The book’s relevance to today is striking. Ngai does not directly comment on contemporary U.S.-China relations, but her analysis offers a historical mirror. Modern Western anxieties over China, often framed as strategic competition, structurally echo the nineteenth-century “Chinese Question,” blending economic fear with civilizational hierarchies. She warns that societies defining themselves through the “othering” of minorities will never fully understand globalization nor escape historical shadows.

Ngai concludes with a line that encapsulates her book’s spirit: “Gold built empires, but the Chinese made them work.” While empires were built on gold, it was the labor of unnamed Chinese workers that kept them running—hands long overlooked, now restored to history not for commemoration but to reveal the costs of modernity.

The Chinese Question: The Gold Rushes and Global Politics was published in 2021 by W.W. Norton & Company. It is more than an academic study—it is a moral and historical reflection. From nineteenth-century goldfields to twenty-first-century supply chains, capital flows and racial hierarchies remain intertwined. Reading this book is not merely an exercise in historical reflection; it is a lens for examining today. The so-called “Chinese Question” has never been about Chinese people—it is a problem the world has yet to confront.

1pmh5v