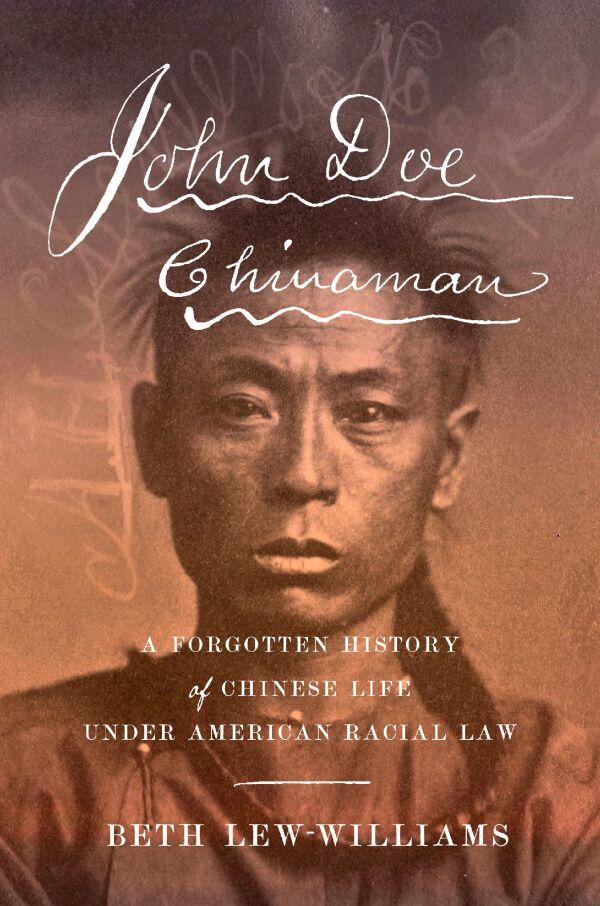

Who is the “John Doe Chinaman”? In 19th-century American West, court records, immigration registers, and tax documents often used this label to refer generically to Chinese immigrants. Their specific names and identities were erased, reduced to “nameless figures” in historical archives. In her recently published book John Doe Chinaman: A Forgotten History of Chinese life Under American Racial Law, Princeton University history professor Beth Lew-Williams uncovers this overlooked history through dusty archival records, revealing the hardships and ongoing struggles Chinese immigrants faced under racially oppressive laws.

Lew-Williams is a professor in the History Department at Princeton University and also a descendant of 19th-century Chinese immigrants. Her personal and family history gives her a deeper understanding of the marginalization Chinese immigrants experienced in the United States. As a child, she grew up in classrooms where the history of Chinese Americans was barely mentioned, which later inspired her to pursue historical research and commit to bringing these forgotten stories back into public view.

While poring over yellowed historical archives, Lew-Williams found that Chinese people were often recognized solely by their racial identity,” collectively labeled as “John Doe Chinaman” or “Mary Chinaman.” This form of anonymization is one of the key issues Lew-Williams seeks to highlight: the law controlled Chinese individuals not only through explicit legal codes but also by omitting or ignoring their specific identities, relegating them to collective stereotypes and institutionalized otherness.

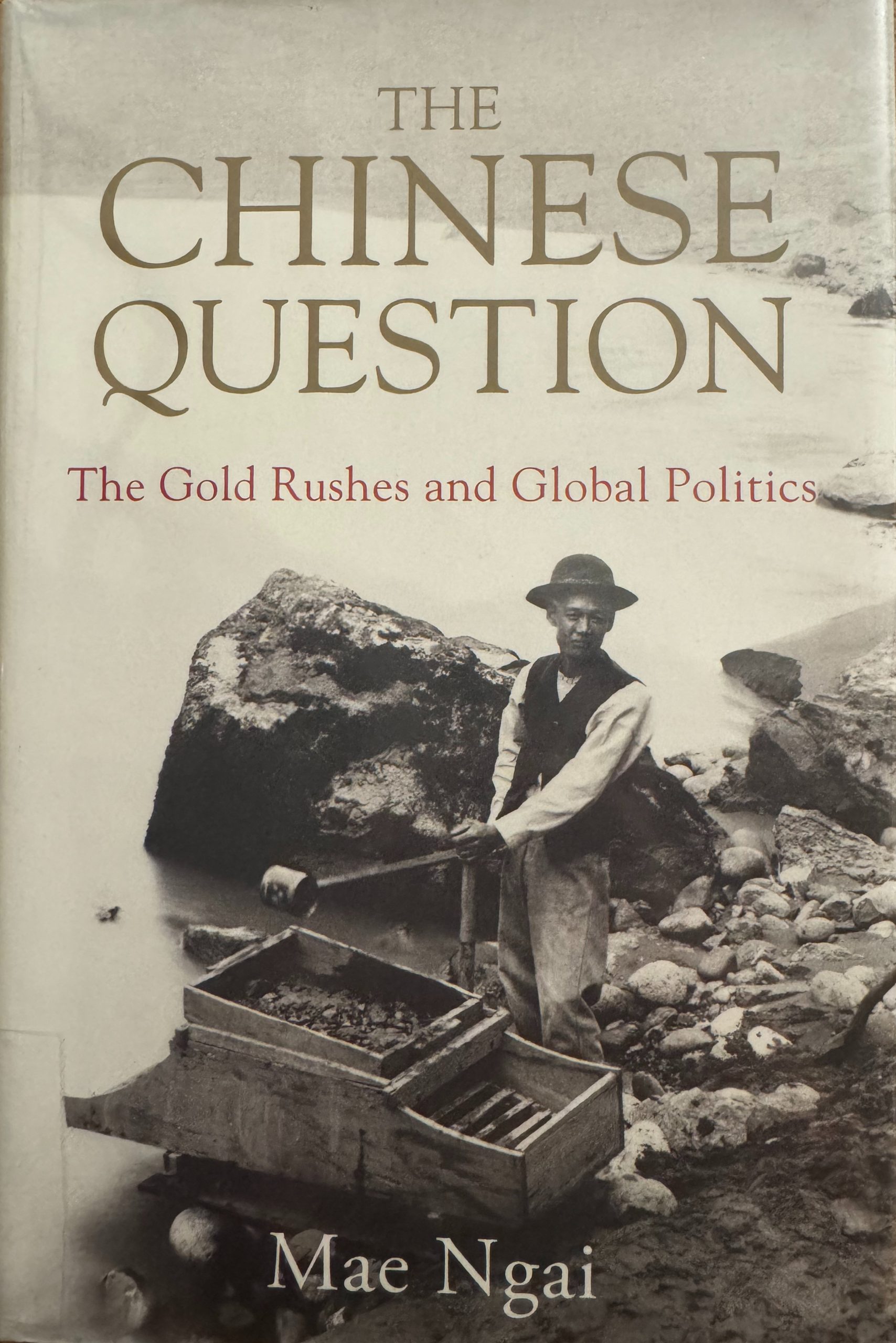

California’s 1852 foreign miner tax serves as a classic example of local authorities using the law to target the Chinese community. From then until the early 20th century, states and localities in the American West enacted over 5,000 laws affecting Chinese people. These laws were not limited to immigration or entry issues—they extended to education, access to public facilities, land ownership, business operations, marriage legitimacy, family structures, public health, and living conditions, touching almost every aspect of daily life.

Those tasked with enforcing these laws were not limited to judges or police officers. Teachers, public health officials, neighbors, and missionaries—whether empowered by law or acting voluntarily—participated in monitoring and marginalizing Chinese communities. Their actions, combined with legal statutes, created a “racial etiquette”: unwritten but widely accepted social norms determining who could attend school, use public facilities, own land, or even marry legally. The interaction of law and custom made discrimination not just an externally imposed force but part of everyday social life, normalized and institutionalized.

Within this constrained environment, Chinese individuals were not entirely without resistance. Lew-Williams’ book documents Chinese lawsuits, legal challenges, and community self-help efforts. They leveraged legal loopholes, challenged unfair laws in court, preserved cultural traditions, and built mutual aid networks to maintain dignity, family continuity, and cultural heritage. In such harsh conditions, these efforts did not always overturn systemic oppression, but they preserved human dignity and community continuity in the cracks of the system.

Compared with federal anti-Chinese policies, local and state laws are often overlooked, yet they had more immediate and nuanced impacts on the daily lives of Chinese people. Whether a child could attend a local school, a family could legally exist, or a store could obtain a business license—these seemingly small legal provisions shaped the life trajectories of an entire community. Lew-Williams’ research shows that without understanding these local laws, much of the restriction and oppression in Chinese-American history remains incomprehensible.

The book is published by Harvard University Press in September 2025. It reminds readers that racial discrimination is not only expressed through major legislation but often lurks in everyday rules and local laws. Systems that appear neutral or self-evident may in fact sustain social inequality. Beth Lew-Williams, with rigorous historical methodology and empathetic humanistic concern, brings the forgotten “John Doe Chinaman” out of the shadows. We are invited not only to remember the lives behind these names but also to reflect on current laws and institutions: do they truly ensure equality and dignity for all.